Emerson Morris

Part of The Disability Museum, an online curation of virtual exhibits created in a Disability Studies class ran by Dr. Lauren Obermark at the University of Missouri-Saint Louis, this exhibit focuses on the similarities in how HIV/AIDS and COVID impact the bodies and material conditions of those within the Missouri criminal legal system, as well as discussing the highly politicized nature of the two pandemics.

Archival records show that the stigma of disease in jails and prisons has a long history that continues to echo forward into today. It’s a tale of two pandemics, and an argument for abolition. Commentary welcome via the QR code provided.

A transcript of an interview with Emerson is below the image gallery

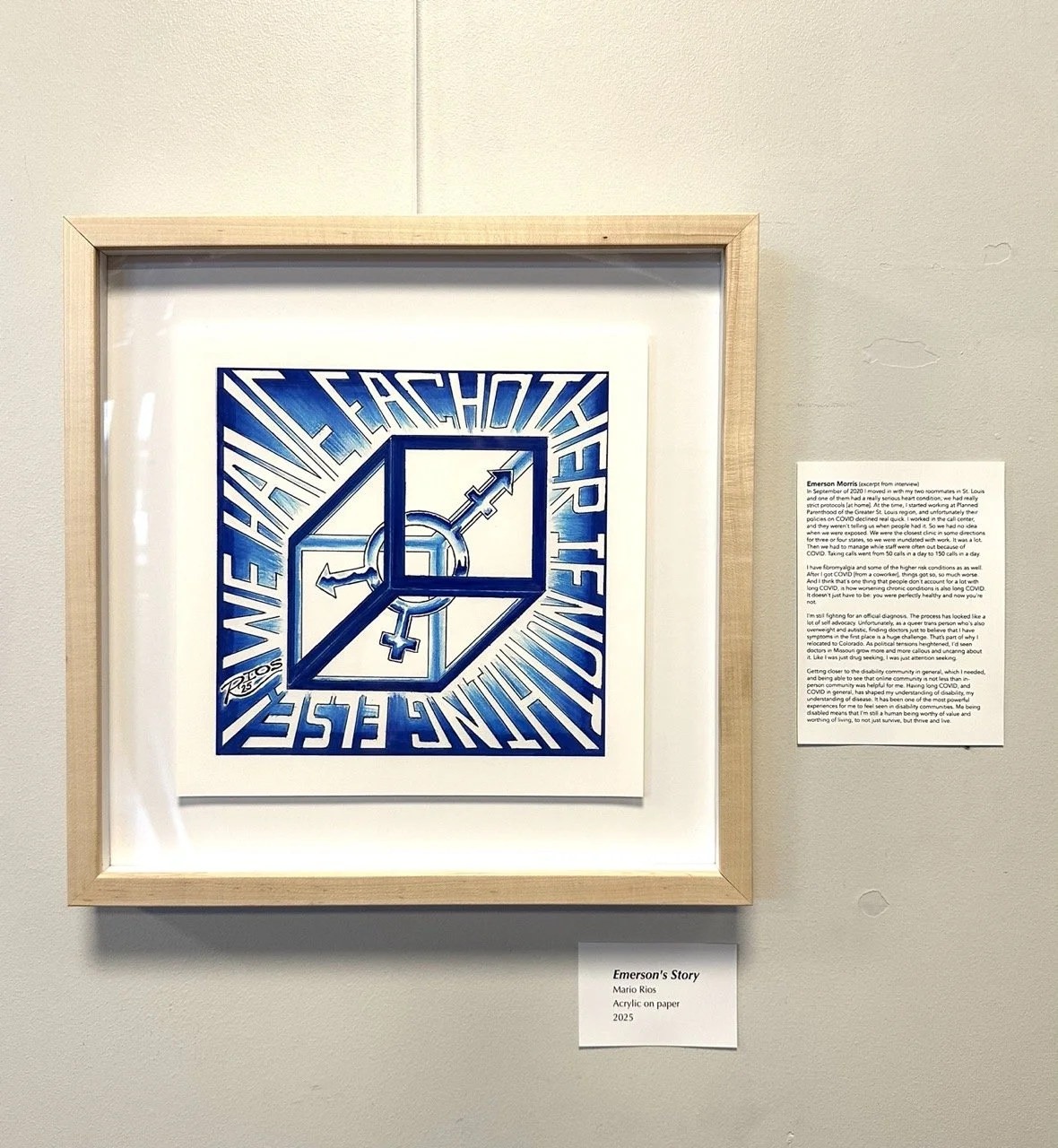

Morris is a disability advocate and poet, recently transplanted from Missouri to Colorado. He recently completed an MFA in Creative Writing and Poetry at the University of Missouri-Saint Louis, and has published multiple pieces on the realities of living as a disabled queer person in the rural Midwest.

Emerson’s story

Emerson's story (from interview on 9/3/25) Part 1

Emerson: As far as the story bit goes, I'm wondering, so I know that your project is primarily focused on long COVID and I can talk about that.

The other thing I would be interested in talking about though is I've done a lot of research about the intersection on how COVID and HIV have been treated and, just the general way that public health handles it and the way that we specifically, it targets certain demographics and things like that.

It was an archival project. So it started with focusing on, it's focused on specifically like prisons and jails in Missouri and like comparing it there. I could also tweak it to like include more Colorado research. I just recently moved here so that's why I didn't focus on that at the time.

H: No, it's totally fine.

E: But yeah, I'll start talking now about the long COVID part and then I'll send you all my research for that, the other stuff and then if it does happen to intersect at all, we can just kind of play it by ear I guess.

H: Yeah, yeah, yeah! Well, so I have actually been working with a group of incarcerated artists to do the illustrations for this show. So like that dovetails really well.

E: Nice.

H: Like, it's so funny to me how this project just things just, I don't know, come together.

E: Fall into place.

H: You know? Um, I think that's something about just kind of approaching things with an open mind and following where the trails lead. So if you don't mind, just if you would share like what your experience having long COVID, if it's just like you want to back up to when you first got diagnosed with COVID or, I mean, you know, some folks don't even know they had it.

E: Yeah. So for me, My attention to COVID really started in September of 2020. So I was a little late to the game because I moved in with my two roommates at the time in St. Louis and one of them had a really serious heart condition. So it was one of those things where we knew like if she got COVID, she was like 99% sure gonna die 'cause vaccines hadn't come out yet. So it was like a really big issue. So at that point in my life, we had really strict protocols. We didn't talk to anyone, like there were no outside people allowed in the house. We didn't go anywhere that was in contact with outside people. Everything had to be, there's this hospital grade disinfectant we used called Odoban that we sprayed on everything and disinfected everything and washed the Doritos and like all those things.

Um, and I remember when vaccines first came out, I was so excited because I was like, finally I can like maybe like go to a farmer's market or like go to a movie or like do the things that I hadn't been doing for the past like almost a year at that point.

And I had been working remotely before that but I finally felt safe enough, like vaccinated, to be, you know what as long as I'm masking in person I feel safe maybe getting a job and maybe like doing an in-person job again because I really loved nonprofit work.

So I started working at Planned Parenthood of the Greater St. Louis region at the time. And unfortunately, their policies on COVID declined real quick. Like it went from “everyone needs to mask, everyone needs to be vaccinated”, to “everyone needs to be vaccinated, and then I guess you should mask if you're around people”, to “you don't really need to mask. If you're gonna do it, we're not gonna get mad at you for it, but we're definitely not gonna enforce it or require it”. And it also got to the point where I worked in the call center, and they weren't telling us when people had it. So we had no idea when we were exposed.

And at the time, my partner then, ex now, but my partner at the time was also immunocompromised. He actually had rheumatoid arthritis and a couple other things that made it like where if he got it, he was also going to get very very sick. And I had fibromyalgia and I had like some of the higher risk conditions as well.

So what happened is I, one of my coworkers was missing and I just had this feeling about it.

So I remember I texted her and was like, “Hey, not to be like nosy, but you've been gone for a couple of days. Can you just let me know if you have COVID?”

And she was like, “Yes, I was actually just about to text you guys. Cause like, I don’t think they told you and that's not fair."

And I took a rapid test that day. It came back negative. Took a PCR test that day and you know, and then the next day I was like, you know, I mean, I'm not having any symptoms.

My rapid test was negative and I was talking about going to see my partner at the time and he was like, “you know, maybe, maybe it'll be okay. It'll be fine.”

And then literally 30 minutes before I was about to leave, I got the emails from the PCR test that was like, hey, it's positive.

H: Oh, geez.

E: So that was, I mean, I'm very glad that timed out the way it did because if I had like, gone to him, we didn't mask around each other because we were masking everywhere else and it was like, you know, it's fine. But yeah, it was really, really scary because it felt like such a close call of like, holy crap. Like he could have died. I could have died. But especially he could have died.

And I'd already had like some health conditions before that. Like I'd had fibromyalgia. I had random, you know, the kind of collective undiagnosed chronic pain, fatigue kind of thing.

They were all like, "We don't really know what's going on with you. You should probably exercise and drink more water and all those things." And I'm like, "Well, I'm doing that. It's not really helping." And they're like, "Well, that sucks."

But after I got COVID that first time, things got so, so much worse. And I think that's one thing that people don't account for a lot with long COVID, is how worsening chronic conditions is also long COVID. It doesn't just have to be you were perfectly healthy and now you're not.

Because my fibromyalgia before that, like I would have flare ups, but it was almost always like, it wasn't super frequent. That's why I didn't like try harder to get like treatment for it, because it was like, I knew how to manage it enough.

But after that, I mean, first of all, when I got COVID, and when I was having it, it knocked me on my ass for like, at least a week. And I had like, severe, severe fatigue, like for like, several weeks after that. And I know that even that is still, like I'm one of the lucky ones, people, there are people that were bedridden for months, and people that still are bedridden afterwards, you know? But I just started noticing that I was suddenly so tired all the time. I was more irritable. I had a lot of mood issues. Because I'd already had some mental health stuff before that, but definitely it got worse after COVID. I noticed like my PTSD symptoms got worse. My brain fog got worse. I I felt like I had to up my ADHD meds to compensate for it, because suddenly it was like, I worked in this call center job where I was taking like a hundred calls a day plus because Roe v Wade had just been overturned.

H: Right. And you're in Missouri.

E: And we were in Missouri. We specifically ran the clinics for all of Missouri and the one clinic that was just across the river in Illinois that could do abortion care. So we were, that one clinic was the closest clinic for some in some directions for three or four states to get an abortion.

So we were inundated with work. It was a lot. And it was like, the cognitive load of it became so much for me.

And also there was security concerns because Roe v Wade had been overturned, the protesters in Illinois realized that that was the one that everyone was going to. So they amped up by a lot. I remember one of my coworkers had like one of them smacked her car with their hand and we all got really freaked out by that.

And we also had our own FBI agent. But it was really scary because our own FBI agent didn't know how to work a Zoom call. And I was like, I don't know how safe I feel having you be my person that's keeping me safe from online and in person threats and you don't know how to work a Zoom. That's a little concerning for me.

I ended up leaving that job and, yeah and it was just…

H: Well, and I’m sure, I would assume given the context that you were working in just at your job, like it would be difficult to prioritize your own health when you know there's so much need so it's like this conundrum that you're wanting to help people but so you kind of push yourself too hard which then makes things worse for you, too.

E: Yeah, and it was really hard, especially 'cause I was the only trans employee in the call center. And I had two coworkers out of five that were actually trying to be trans competent.

They weren't perfect, but they at least tried to use people's pronouns and tried to do other things. And the other ones were the kind of people who would intentionally misgender people if they were pissing them off, or they would specifically not, they wouldn't go, not even the extra mile, they wouldn't even do the bare minimum for trans patients.

And I remember having to initiate these trainings and like ask HR like, "Hey guys, this is not okay, this is not okay." And like get pushback for that.

So when I finally left Planned Parenthood, it was awful for me because I just kept thinking like all these patients that aren't, that already, like in the same way abortion care wasn't accessible in several states in some directions, trans healthcare wasn't either. You know, like you had to travel like from Oklahoma to Joplin, Missouri or from Arkansas to Springfield, Missouri, or all these different things. And it was awful to have to leave. But because I knew I couldn't do it anymore, I was having panic attacks every night. And I was just exhausted all the time. I literally would come home, and I could barely make myself food.

I couldn't really like, my apartment was trashed constantly, like horribly, because I just couldn't make myself do anything when I got home, because I was so stressed and exhausted, both from long COVID and just from like the intensity of the job.

And it was, like, I think people also don't think about the way COVID impacted care like that, because not only did we have that, but like you had to manage all of that while your coworkers were every once, were often, not even every once in a while, but like often like having to get out, be out because of COVID. So then, you taking calls went from, oh, I'm taking 50 calls in a day, to I'm taking 150 calls in a day. And you would see, we had this like call board where you'd see all the dropped calls and it was in the hundreds.

And I remember just seeing that every day and just feeling like, "Holy shit, like I'm just failing all of these people." And like, and obviously like that's, I can recognize now that like that's not, it was the system that was failing, not me, but like it's hard to shake that feeling of like, "Holy shit, all these people are trying to get help, trying to get care in this time that's really uncertain with healthcare." and they can't because we can't even answer the phone.

H: Yeah, 'cause you were understaffed.

E: So understaffed, yeah. Because, yeah, and that's why I'm still a little bitter about Planned Parenthood, I'm not gonna lie. But it's one of those things where you can't really say anything about them because I don't ever wanna be the person that says, yeah, Planned Parenthood sucks. And then they get hassled more than they already are.

H: Right, well, and it's hard to say anything and include the entire context, right?

E: Yes.

H: Like no organization is perfect. This is, there are humans involved, you know.

E: Yes.

H: So, especially when you're working in a high stress environment.

E: Yeah, and nonprofits just unfortunately in capitalism, like they fill in some gaps, but they also make the gaps worse in some cases. Because it takes away the power from like the grassroots kind of community…

H: Yep.

E: orgs. And yeah, so, and then from there, like after I got away from my parenthood, my health got a little bit better. But unfortunately for me, this past year, I got COVID again in February. We're not really sure where I got it from. It just kind of presumably from like going to the grocery store or something.

You know, one of those places where like I mask in public, but unfortunately one way masking just isn't, it's not effective. Like it's better than nothing, obviously. But people just don't talk, like that's what pisses me off so much about people being like, “oh, well, if you're like worried about COVID, just mask yourself.” And I'm like, if you saw any of the data about how one-way masking works.

H: Well, and especially one-way masking, one-way masking in environments that don't have good airflow, et cetera. Like all the things that we could do structurally didn't happen.

E: And as someone who's like more left than liberal, it also makes me frustrated because the reason that COVID it feels like, just became like, oh, the pandemic's over was because the liberal Democratic administration with Biden just wanted the win so bad.

That instead of choosing to like actually help their constituents, it was like, "No, we're just gonna pretend it's all over and it's fine because we won.”

And it's like, no, that's not what happened. Like, it's not.

H: Yeah. It really frustrated me, when it was like, "Oh, we have vaccines, so we're all good now." And I'm like, "That's not how vaccines work." Especially when you don't have majority population using that, you know what I mean?

E: Right.

H: The numbers matter. Herd immunity is a specific thing that is not happening, especially when you have… And I'm not diminishing any type of, like there are vaccine reactions that happen, like obviously, that’s a thing.

E: Yeah, but that's not the main reason

H: Not at all not at all.

E: Yeah. And the fact that masking became so politicized, which. I mean if you if you look at the history of disease and things like that, it makes, you see why it was politicized, you know, but it doesn't make it suck less

H: No.

E: That like our bodies and like our health became a topic of like, politics and not… like obviously everything's politics to a point, right?

H: Yep.

E: I don't agree with the idea that anything really is apolitical, especially today's world.

But the idea that it became controversial to protect each other and try to help each other and also, in this time when capitalism is getting worse and hyper individualism is getting worse.

And so suddenly all the community care that was there, maybe for like the HIV pandemic, and these other big disease spreads we've had where community stepped up and community helped each other. Like, unfortunately, that's so much less with this.

And I also think it's interesting because the people that I do see caring about it are the people that understand the history of it. So the ratio I see of people in my COVID cautious communities of cishet people to queer people: there's so many more queer people. Which is sad to me because I'm like, it's not like straight people deserve to not get COVID too.

H: Well, and straight people got HIV and get HIV too.

E: Yes.

H: It’s such a misconception.

E: Yeah, that you're safe.

H: That was a huge thing that we tried really hard to focus on during our conference that we did in 2023 and the celebration in the 40th was to like recontextualize like there were women who were getting AIDS, there were people, like not just gay men.

E: No.

H: You know, and not just white gay. Like the numbers say vastly different things.

They might have been the loudest and the most in public but they had the privilege to do so. Which is like in one way a good thing because they somewhat got listened to, a little bit. You know?

E: But also then it left behind all the other people.

H: Absolutely. And like the story of the activist story is very complex, like the people that I talked to— there are like old wounds that are still very sore you know?

E: Yeah. It’s hard, yeah I mean.I believe it was Miss Major who had this interview with the New York, I believe, I think it was the New York Trans oral History Project or something? I don't know if that's exactly what they were called or not. But she talked about how like Stonewall parades were happening and even like after like the HIV pandemic like really started like becoming a really major issue. Like she remembered seeing all these people that had never shown up for her thing, and the black trans queer sex workers who were most at risk for HIV and most at risk for these things. And they just got completely left behind in the name of like rainbow capitalism.

And I think that with COVID it's been a very similar story of the disabled people who are most impacted, which is also a racial issue. Like, we see the statistics on how Black folks are way more impacted. They're hospitalized more, they die more, they have more complications, like there's all these different things. And the same thing with trans and queer people, like you are more likely to have complications, you're more likely to be hospitalized.

And I don't think people even think about like the risk factors that they have listed, on the CDC website, which is like, I think most COVID cautious people know at this point is not complete.

Like it's just not. But they even they list like, depression is a factor for COVID. You know, anxiety is a risk factor for COVID, autism is risk factor for COVID. Being like, having a BMI, which is bullshit anyway, but like, you know, being classified as obese, that is a risk factor for COVID. There's all these things that people don’t, like people don’t think about how like, how many things are putting them at risk. And they don't seem to understand that it's not just, first of all, it's not just that there are affecting other people's health, which in and of itself is also really fucked up. But even if you're just thinking about yourself, people just don't seem to be realizing like how common and easy it is for them to be the next person with long COVID and how they a lot of them already have it. There's so many people that I know that are like, “yeah, I don't know why I'm tired all the time now. Geez, it's so weird that I get sick all the time now.”

And I'm like, you have long COVID. That's why you're sick all the time. That’s why you're fatigued. That's why, now you have chronic pain. That’s why, now you have, you know, MCAS. That's why, now you have fibro and like all these different things that we know come from that. You know, we've seen the research and it's happened already.

PART 2

And also what I like to contextualize with people especially is if we're looking at timelines of diseases right now, we're in 1985. In terms of like when HIV started, when like that became an issue with COVID now, we've had five years. That’s nothing in this world. That is not enough time to research, really, a lot of things.

H: Yeah, I mean, really, the only thing that's different is the fact that we had a vaccine.

E: Yes.

H: Right? Like, that's the only thing that's different. If you look at, because especially with viruses, like, vaccines only do so much.

E: Yes. And we are still working on figuring out, like, with the long term, we don't have long term consequences of long COVID yet.

H: We don't even have that for HIV/AIDS.

The folks that I've worked with, they just had a conference this fall about like specifically the research on folks who are older, who have had HIV for a long time or even a new infection, you know, like newly diagnosed, like who are older, like what does it look like to be older and have this virus?

How does aging impact the effects of this virus? And like no one knows because so many people died there's like so little research. It’s only now that those people have gotten older, the survivors. It's just like there's so much we don't know. And not that we should live in fear, but…

E: You have to realize that like this is not the end stage right? We're still in the beginning stage. You know, like this is still the very early side of it.

And I also think about that a lot in the context of children and especially how children didn't have really severe infections when they were, um, when it was first happening, which everyone seems to laud as this great thing. And I'm like, that's not really good because it just means they weren't having immune responses.

H: Yeah. Or like chickenpox and shingles, you know, I mean, there's so many things that have post viral effects. This is a novel virus; we don't know what those might be. So having a little caution would be good.

E; And what we do know is terrifying. We know it causes brain damage. I remember there was one study I read where they had people that had already had MRIs or brain scans prior to having COVID for whatever reason, just having them on file for whatever reason. And every single person that had one before, that they took one of after, that had had COVID, had brain damage.

H: Interesting. I have those scans! The before ones.

E: Yeah, and I'm like, I don't even understand how that's not enough to just scare the fuck out of people. Because for me, losing my mind, that's the thing that scares me the most. 'Cause my body, that's scary too. It's scary in different ways though, because with your body, you at least are aware of what's going on. I think about how much prefrontal cortex damage is showing up in COVID research, how much damage there is to decision making centers, and how anecdotally I'm seeing people become more callous and more reckless. I don't have a study that necessarily says, “Oh yeah, for sure, that's why that's happening." But, as we creep more and more towards fascism—and not even creep, we're running towards it at this point—I think about how much of that is influenced by COVID? how much of that is influenced by the fact that people have fucking brain damage?

H: Yeah, that would be interesting. To like, 'cause especially if you look at, you know, 100 years ago with the flu pandemic and the rise of fascism.

E: And the rise of fascism.

H: Interesting parallel.

E: Yeah. Yeah.

H: Wild. Okay.

Is there anything additionally that you'd like to share specifically about your experience?

Like, how did you get like an actual diagnosis? What was that process like?

E: So as far as, like getting diagnosed with COVID or long COVID?

H: Long COVID. What was it like? How did you?

E: I’m still fighting for an official diagnosis.

H: I was gonna say, did you, A- have you had a diagnosis? B- how has it been finding support and potentially treatment or even acknowledgement? 'Cause I know a lot of people, I mean, there's just a lot of providers that aren't informed to be able to look for the, or I mean, we don't even have a diagnostic system really. Yet.

E: Especially because it affects so many different systems in the body. I mean, everything from erectile dysfunction to IBS to hair loss to brain damage to organ damage to like, all these different things. So it's not really easy to just say like, oh, point to any one thing, here's the test for whatever. If we, which we also just don't have tests, but yeah.

So for me, the process has looked like a lot of self advocacy and, unfortunately as a queer trans person who's also overweight and also autistic, finding any, finding doctors just to believe that I have symptoms in the first place is a huge challenge.

And that was part of why I relocated to Colorado. As political tensions have heightened I've seen doctors in Missouri just grow more and more callous and like uncaring about it. I saw the way that like I would go to the ER because I was having heart palpitations and a lot of dizziness and disorientation from the POTS that I've developed like from COVID. But I can't for sure say that it's from COVID, but it feels pretty evident because I didn't have the issue before. And now I do. But the way that all of that got so much worse for me and the way that they would look at me like I was just drug seeking, I was just attention seeking. And I'm like, I don't wanna be here.

I don’t. I don’t. If I could avoid the hospitals forever, if I could never go to the doctor again, I would do that in a heartbeat. But I also recognize that that doesn't work. You can't just choose to be like, well, if I don't go to the doctor about my health, it's like, it's not happening.

H: Yeah, you're like, "I'm not here for fun. I’m not here to amuse myself," like, no.

E: No, it's a horrible thing. And also it costs so much money.

H: It does.

E: And like, I don't know why people have this impression that it's something I'm just doing for the fun of it.

But yeah, so I have had doctors here that have been more willing to at least acknowledge that I have POTS, at least acknowledge that I have fibro. But I remember some of the earlier doctors I saw in Missouri were definitely like, would just tell me, “Well, I think you just have like, you know…” they wouldn't even tell me I had fibro at times. There was a doctor that tried to fight me on that. And I was like, “I clearly have it. I've been diagnosed with that already.

So I don't know why you're telling me this diagnosis that I already have somehow has magically vanished. That's not how that works.”

And then as time's gone on, it's just gotten harder and harder for people with long COVID.

I mean, and to go back to Missouri: in St. Louis, they recently closed their long COVID clinic. I’ve seen so many long COVID clinics that are closing because there's no funding, because there's no support, because there's no way for politically, or financially, or whatever the reasons are.

And the reasons are numerous for them to continue on with that work, which sucks, especially because that's going to be all of this research that we don't have. All of this data that we don't have. And if you don't, people don't like, that is one of the biggest challenges in disease research and in trying to fight disease and things—you need data. You need, you have to have the like, what is happening. And if you don't know what's happening, how the fuck are you supposed to fix it?

How are you gonna do anything if you don't even know what's going on? So it's just, it's wild to me that people, that this is where we're at. It's so disheartening to me that this is where we're at. But the one ray of hope I do have is seeing how the COVID cautious community has stuck together and has continued to care even for people that don’t. I'm part of Mask Bloc Denver and we do a lot of community outreach. We’ve been trying to table a lot of events, events that are maybe mask required, maybe aren’t. But then we try to have conversations with people and say like, “look, if you were masking in 2020, why aren't you masking now?”

You know? If you were masking then, or even if you weren't masking then, still: why aren't you masking now? What has changed and what has made you feel like it's okay to not do this?

And would you still feel safe doing this if you knew all the research behind it? If you were seeing the things that like all of… And the way that all of these COVID cautious people have to become our own scientists, our own researchers, our own doctors, because there isn't anyone that cares, and like this, these medical systems, so we have to care for each other. And we have to become that for each other.

And the same way that, during the HIV pandemic, like, when that first started, people had to do their own research and had to become medical experts for shit that they had, they didn't know. I mean, like, these were people that didn’t initially have any medical training, right?

H: Yeah, or at least to gather the data and be like, "Look at this, doctors. Look at this." Like, yeah.

E: Yeah. And that was hard.

And that's still what we're doing today. I'm still showing up to my doctor's office with five studies in my back pocket thinking like, "Okay, well, if they don't listen to me about this, I can pull out this one. And if they tell me that this is wrong, I'm like, no, this is actually right.”

And I shouldn't have to be more informed than my own doctors, but I am.

And they also, the way that that threatens them, and the way that they get so defensive about that makes it even harder to access care because I'm like, “I don't think that you're a doctor that's incompetent. I think you just don't keep up with this research.” I think you just don't see what's going on.

H: Well, and then it's hard because the research isn't prevalent, right?

E: Right.

H: My partner is an endodontist, so he's a dental specialist in root canals, which is infectious disease. Not infectious as in it can spread to other people, but it's usually localized infection.

He has to keep up on the research, but a person can only do so much. I can see it from both sides in a way. Doctors have it hard, too, because they have to keep up with so much, and it's constantly changing. I just wish there was a bit more openness and kindness and like, “oh let's look at this together,” and you know, camaraderie?

E: Yeah, instead of just like, “oh you're gonna be Dr. Google. You're trying to like replace my job.” And I'm like, “I'm really not. I don’t wanna be a doctor.”

H: yeah, “I’m just trying to help you out here, man.”

E: I don’t. I don't want to do your job, that sounds awful to me. I would just like you to do your job for me.

H: Yeah, yeah, it's really difficult. Okay.

Have you found that Colorado has been a bit more amenable to like, the treatment you've been trying, or community support, that kind of thing?

E: Interestingly enough, in some ways, the COVID cautious community here seems smaller than it was in St. Louis, which is interesting to me. Because I mean, you would think that it would, having it be like a red state that I'm coming from, that the COVID, there would be like less COVID or more COVID cautious people here or more people that are like doing that work.

And I think like, in a way, yes, but it feels like the reason that there's more isn't just because like on a ratio basis, it feels more like Denver just has more people than St. Louis does.

So just like by statistically speaking, you're going to have more. But if you're looking at like the percentage of the population that seems to care versus the percentage that cared there, I mean, it also really depends on where you're at in Denver.

Like in Aurora, where I’m, where I'm living, I'll walk into a grocery store, and I'll see like at least a few people mask pretty much every time. They're not always masked in good masks, sometimes it's a surgical, sometimes it’s cloth.

But there's at least people that are recognizing like, hey, we're all getting sick and we need to do something about this. But I'm told that if you go to like Longmont, if you go to like some of, if you go to Boulder, you know, like they're, it's just non-existent.

H: There’s a handful, but yeah, I hear ya.

I have noticed this like late summer, like when we tend to be in more of a upswing, I've noticed more people masking. especially older folks, which, you know, statistically, being in a more healthy, statistically wealthy population, then your more at risk people will be elderly folks.

E: It's also interesting to me how I feel like the richer the area, the less they care about COVID.

H: “We got money to throw at the problem—it’s fine.”

E: They can afford to not care.

But like when you're an entry level worker, and you miss a day of pay, you're like, “Fuck." You can't just be like, "I'm good, it's fine if I get COVID.” So I think that plays into it too.

And also the fact that, I mean, Denver is definitely a little bit more crunchy than Missouri is.

There’s definitely a lot more like alternative medicine emphasis, which isn't necessarily bad.

But it's just, I've found that the Venn diagram of the people that are very like alternative medicine and holistic medicine and like we do yoga, we do all that. And the people that are anti-vaxxers, like "they're putting chemicals in the milk and I have to drink raw milk.”

And I'm like, oh, that's not.

We can do like holistic herbal medicine. There's also points where we have to realize that like, if you're having like trouble sleeping, chamomile, if you're maybe having like a little bit of pain, There's like Willowbark can help.

If you have an infection, get some fucking antibiotics. There's levels of it.

H: So you mentioned that you have some chronic conditions that were prior to-- that were worsened, et cetera, from having long COVID. Adding that to your cocktail, right?

Has there been anything really specific that has either-- has been new that you've learned or like, you know, kind of lit a fire in you or that changed due to this experience?

E: Oh yeah, so much. So I definitely like, I… Part of it also got me closer to just the disability community in general, which I needed.

Like I, I mean, I've been autistic, obviously, my whole life, it’s not like it just developed, but I've known I was autistic since I was like 10. But I never really understood what that meant. I never really understood what went into that, how disability affected that, how disability justice mattered in those kind of things.

And once I started getting sick, getting access to this community, and people that were like, “hey, this is what disability justice looks like. This is what we can do to keep each other safe and what we should be doing to keep each other safe.And how these things impact you.”

Here's how, seeing content online about how, hey, if you have digestive problems, that can be because of autism. Hey, if you have issues with this specific thing, that can be because of these things you already had. But there's just so little knowledge about it and so little activism that is publicly facing in the sense that people are paying attention to it. There's a lot of activism that's happening that people are trying to be public facing, but the amount of activism that gets seen by the public is just so little.

And the way that also online communities have become so disparaged, I think is really interesting in a disability context because for some of us, that's all the community we can access. We can't go hang out in huge crowds. We can't just go to a coffee shop and be like, let's sit around unmasked and hope nothing happens. That's not how that works.

So it's being able to see that online community is not less than in-person community was helpful for me a lot. Which some of that I already had a little bit of context for, being queer. Because I think from, there’s a little bit of that same kind of emphasis on like, "Hey, we know that you're not going to find people by you all the time." So sometimes you have to go virtually, you have to find people that are across the country or across the world even, but they're the people that you're going to have, to rely on.

And the way that this, that having long COVID and COVID in general has shaped my understanding of disability, my understanding of disease. It baffles me now that I used to go out and just go to a concert with no mask on, even without COVID existing, like the flu, like all, there's a bajillion viruses out there that I am so lucky I did not catch. And in some cases I did catch them constantly. I was sick all the time when I was a kid, I was a very sickly child.

And it's just so interesting to me that all, there are plenty of other cultures that value, I mean, that value masking and keeping each other safe and when, and staying at home when you don’t feel well, and we just don't.

Like on an overall level. So one of the things that really helped me was just helping me understand, finding people that understood, finding people and that I didn't feel so alone anymore. It has been one of the most powerful experiences for me to feel seen in disability communities. For a long time I wouldn't call myself disabled. “I have autism but I'm not disabled. That's not me.”

*garbled audio* like everyone thinks it is. It's not just any one thing. If we're counting, I didn't know. I've seen estimates between I think 40% of Americans are disabled, something like that.

But if you include all the things that actually disability encompasses, I have to think that that number's gotta be way higher because I mean, especially in late stage capitalism, who the fuck doesn't have depression right now?

(both laughing)

E: Who doesn't have anxiety? Who doesn't have all these things? And those are all disabilities.

PART 3

H: Even just the mentality around it, right? “You’re like, I can push through,” you know? So essentially what you're saying is this helped you see not that being in the disability community, to see it as like a, not a badge of pride, but it's something not to be ashamed of.

E: Yeah, and to be proud of too. I will say that. I would go that far. I think that it's something that disability pride, and I think people misunderstand what we mean when we say disability pride. Do I mean, "Yay, fibromyalgia, I think everyone should have fibromyalgia, it’s so fun”?

NO.

Do I think that me being disabled means that I'm still a human being worthy of value and worthy of living, and worthy of having a high standard of living, of being able to survive and not just survive, but thrive and live. And that's what, to me, disability pride means. It's not like, “yay, we love diseases!”

It’s like, hey, we still are human beings that deserve to exist and deserve to be happy and healthy as much as you.

That's the thing for me is like, it's taught me that I am not a morally bad person because I've had these challenges and because I've had these experiences. And in some ways it's made me stronger. And in some ways it's made me a better person, I think for being able to say, I know what it's like to be marginalized in these ways.

And not that being oppressed is ever a thing that makes you stronger. I hate the idea that “trauma makes you strong.”

H: Yeah, yeah, yeah. It's like glorifying it or something.

E: Yeah, but there is a level of empathy you learn with that.

Because you have to. You don't have a choice because you need people to care for you.

So even if you're just looking at it at the super individual level of “I just need people to care for me”. You're not gonna get that if you don't care for others.

H: Yeah, yep.

Okay, and I just have one more question. Any resources you would like to share?

E: Yeah, so in Denver, Mask Bloc Denver and COVID safe Colorado are really helpful.

We, both organizations do individual mask requests, you can get free masks and free tests.

Another thing that Mass Block Denver does is more like tabling at like local events. And COVID Safe Colorado, they host their own events. I know that they've got a queer Halloween event coming up that's gonna be masks required that's gonna be really cool.

And I think in general, like, really just, there's so many good content creators you can find that are talking about this stuff. In Colorado, the people that I could send you to be like, follow these people on Instagram, follow these people on TikTok, you know. And I actually probably will do that.

But, yeah, there's so many people talking about this and I think it's, that's what brings me hope. The idea that we're not just dying quietly and letting that go. We're saying, hey, we're still here and we're still gonna care for each other even if other people won't care for us. We have each other if nothing else.